Photo © Eithne Owens

During my Substack break I had a quick trip to New York City and a long overdue visit to the American Museum of Natural History. My friend and I didn’t have a huge amount of time, so we asked the incredibly helpful and friendly docent for her top tips. (One of which was the new Gilder Wing, and once the docent told us that people often get confused and call it the Glitter Wing … well, it will forever be the Glitter Wing in my heart).

High on the list of highlights were the famous dioramas. These are often referenced in articles, in images. Some of them (the Akeley Hall of African Mammals dioramas) date back to the early 20th century. They are enchanting. And what I have spent hours trying to figure out is … why.

20% … they don’t make them like this any more

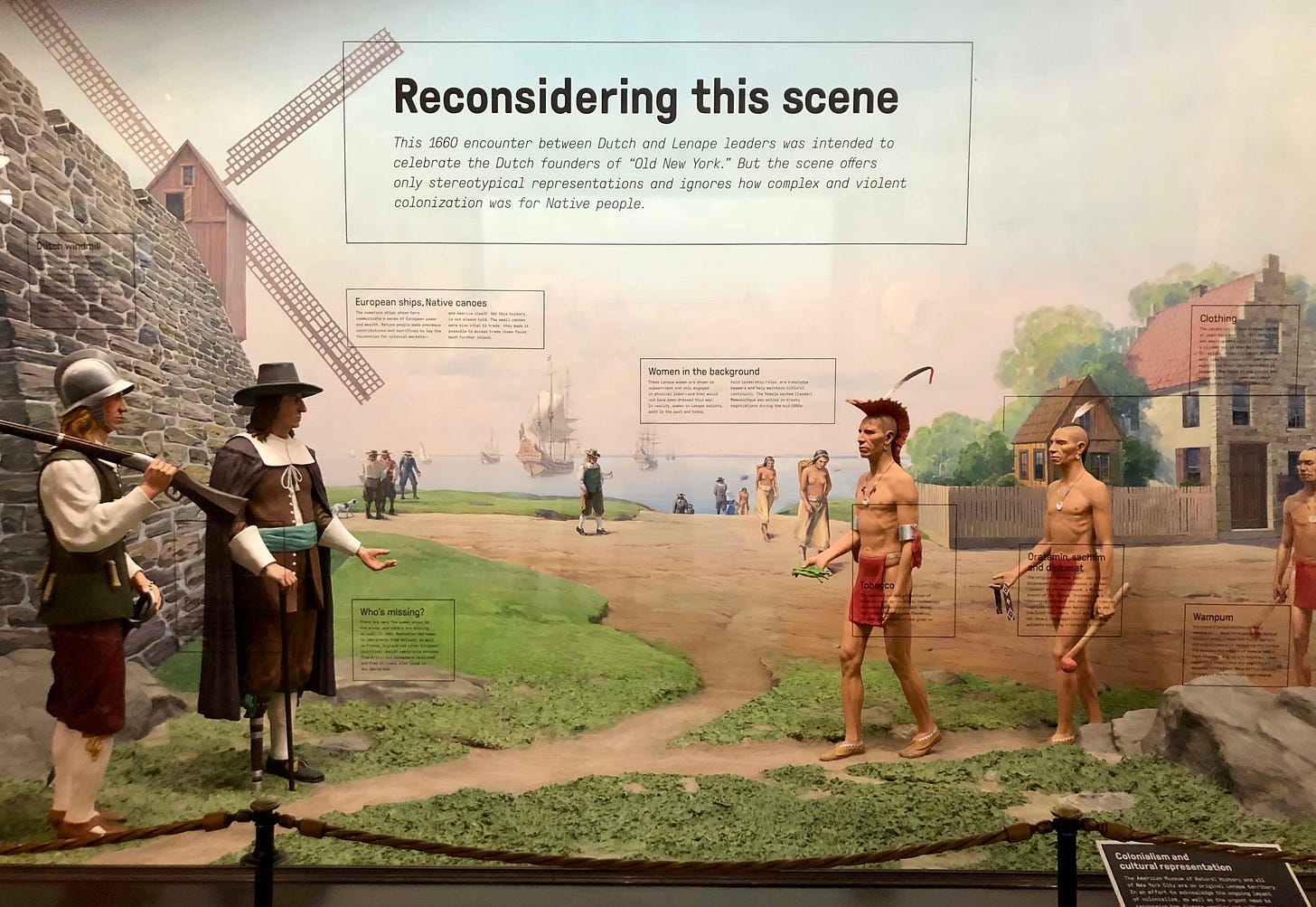

By the late 20th century dioramas had fallen out of fashion; many were removed from display. Some (including the 17thcentury scene below) are distinctly problematic. But in spaces that can be heavily mediated by screens and projections … there is a feeling of sensory relief when you experience something analogue, something physical, something different.

10% … we like things in 3D

I’ve often said this in relation to museums generally (I mean, many people have said it). Of course media have an important role in interpretation, but one of the greatest assets museums have is the appeal of in-real-life three dimensional things, not 2D versions on screens. I think the dioramas, because of their inherent physicality are part of this appeal. My friend and I spent quite a while parsing the 21st century version of the diorama in the Hall of Biodiversity, a display mixing specimens with a projected rainforest scene. In theory it seems like a good idea, but it didn’t have any of the transportive charm of the older dioramas.

20% … charm

Speaking of charm. The original dioramas have it in spades. There is something about the painstaking detail, the care evident in the placements … these are displays with personality. In a world of often bland and beige museum displays, they stand out. And yes, some of this is nostalgia for the way we imagine things were (the museum of the museum), but I do think some of it is about a less contrived, less sanitised way of presenting things, when the marks of the makers are present. (Although I do wonder how evident these marks would have been to audiences 100 years ago.)

30% … artistry

The landscapes are extraordinary. You could take the dioramas out of the museum, stick them in the Met, call them art. (Or stick them in MOMA and call them post-modern art.) But I took dozens of photos of the details, the brushwork, the colours … they conjure up a sense of place that’s amazing now, let alone 100 years ago to audiences who weren’t used to seeing three-dimensional images of the savanna or the rainforest in glowing colour.

20% … X factor

Times have changed. Our views about commissioning displays of stuffed animals have changed. It’s hard to imagine something like the Hall of African Mammals ever being created again. But I have a Pinterest board called ‘Dioramas Reinvented’: testament to the amount of time I’ve spent thinking about how existing taxidermy collections could be re-presented … from the minimal (no backdrop) to the media (projections or video environments) to the augmented. But nothing I’ve seen ever grabs me in the same way. Maybe it’s because once you go post-modern, you can’t go back. I’d always want to add a layer of cleverness, some kind of comment on the view. Whereas the beauty of these dioramas is that they’re not trying to be clever: they’re inviting you, pure and simple, to witness something wonderful.

Photo © Eithne Owens

PS

Photo © Eithne Owens

Not all dioramas are wonderful, of course. On a different level of AMNH (literally and metaphorically) we spotted this one. I like the way the Museum has layered interpretation over it, showing we can hold space for the historic and the contemporary together (although nobody passing by seemed to notice, possibly because the text on the glass was a bit hard to read). I think, though, there’s a fine line between showing views have changed and turning the views of past museum makers into curiosities in and of themselves—something for us to point and laugh at, without enough humility to acknowledge that our own views may be curiosities in the future. Maybe this is one diorama that could be safely put in storage.

Food for Thought

An interview from 2003 with an AMNH diorama artist

A behind the scenes look at the dioramas

And a great long read from the New Yorker about the dioramas

And if you want an even longer read (hey, it’s Christmas time!) I commend to you Mieke Bal’s 1992 paper Telling, Showing, Showing Off which takes AMNH as a jumping off point to talk about the museum of the museum, metamuseology, narratives, artificial nature/culture divides … you know, all that good stuff.

The dioramas in Russian Museums were remarkable, if you ever had the chance to visit some of the War Museums.