This is something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. So long that I felt that I couldn’t even begin to write about it unless I researched it for months on end. The irony is that avoiding ‘done’ in pursuit of ‘perfect’ is actually at the heart of this particular issue.

How do you end a story in a museum? How do you elicit a sense of conclusion, of closure?

Exhibit A: Eat, Pray, Love

This is a book that launched a thousand memoirs. Woman goes travelling and finds herself via pasta, prayer and a new man in her life. If you haven’t read it, I should say that Gilbert is an excellent writer, and there’s a reason that this book was a best seller. But I have always struggled with the ending, particularly in view of the little I know about Gilbert’s personal life. [Spoilers follow] The story concludes with Gilbert finding love with a charming Brazilian. A book about finding yourself wraps up with the neatness of the classic marriage plot. Everyone loves a happy ever after, right? And, to be fair, it is one of the time-honoured ways of concluding a story.

Except that this wasn’t the ending. Eventually Gilbert left her then husband for another relationship. And, you know, that’s what life is like. It’s messy. Things change. Other people are less obsessed with the endings of quasi-self help memoirs than I am.

You’ll have your own example, but I do think of this book as an example of a particular truth when it comes to non-fiction storytelling: endings are really difficult to deliver in real life stories. As Frank Kermode points out in his classic piece of literary criticism, The Sense of an Ending, the only true ending in life is death. All other endings are temporary: commas, not full stops.

I don’t know if this is true for all museum makers, but I know that part of my own struggle with finding an appropriate ending is this awareness that nothing is ever fixed. It’s hard to draw a conclusion when you’re aware of everything that comes afterwards. When you’re aware of how narrative (in fact, the whole of history) has been used to impose order and meaning, and with that exert power, over individual lives. Narrative is the brush, tidying up messy events.

But whatever the root cause, I can see the symptoms of ending-avoidance in exhibition after exhibition. So many experiences that avoid drawing any conclusions, with the result that they fizzle out.

Does it matter if there is no ending? Well, if you call what you’re doing in the museum ‘storytelling’, then yes, I’d argue that it does. There’s a reason that kids learn the mantra, ‘a story has a beginning, middle and end’. The most basic version of the narrative arc is that there’s a status quo that gets disrupted; disruption leads to resolution; resolution results in new status quo. My best friend is Mia. Mia moved to a different city. I made friends with Jack. Jack is my best friend. The ending—the resolution that leads to the new normal—is an important part of the structure. Frank Kermode again: ‘men, like poets, [are born in the middle of things] and to make sense of their span they need fictive concords with origins and ends, such as give meaning to lives and to poems.’ We need an ending to make sense of … everything. Without some form of ending, the story feels incomplete, unsatisfying. It doesn’t make sense.

So for me the questions is not, do we need endings in museums, but, how do we do them well? Where do we start to find the end?

1. Ask the audience

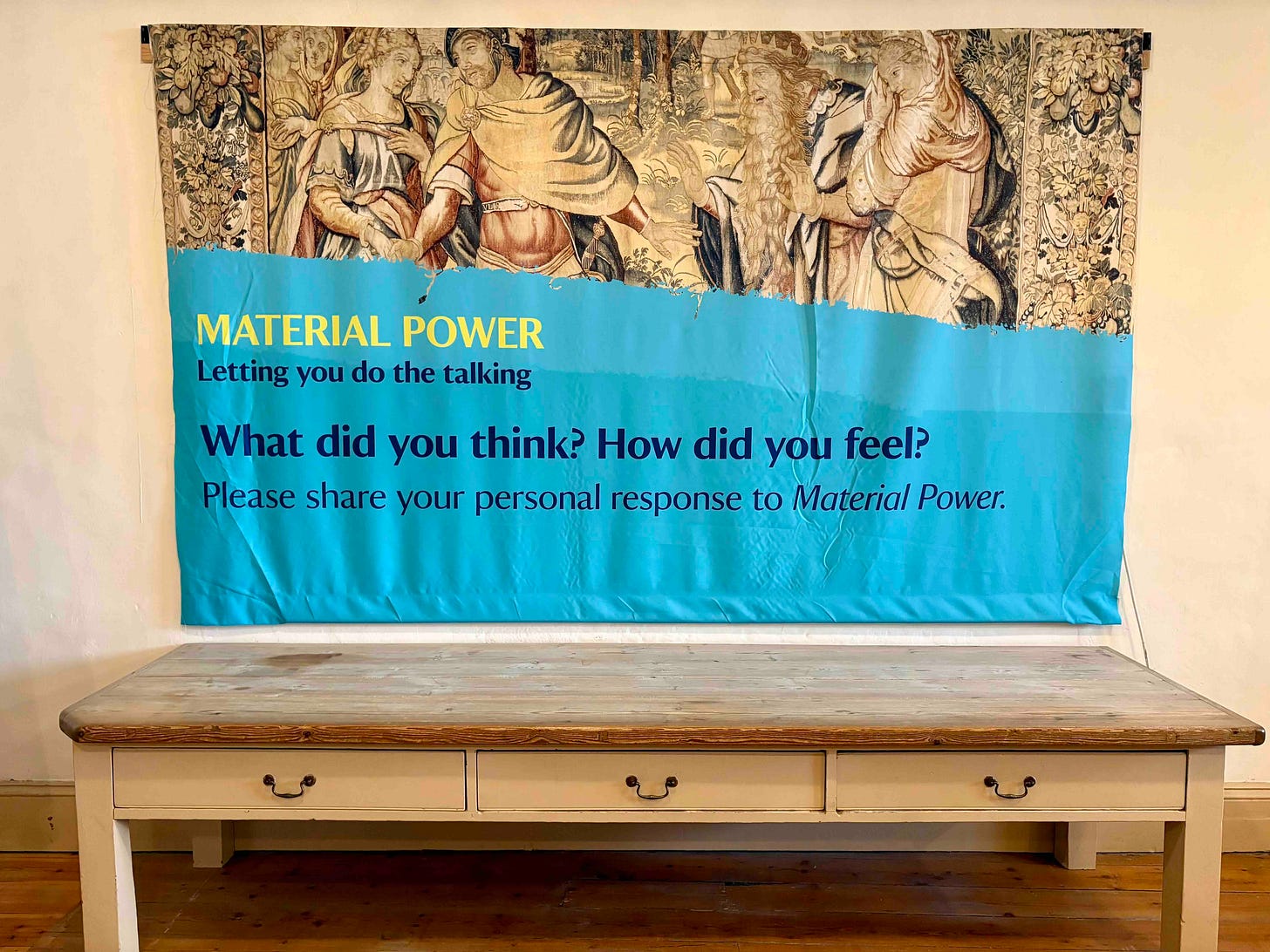

I’ve seen numerous post-it note walls, reflection spaces, resource spaces that attempt to address the challenge of how to offer some kind of conclusion to an ever-moving river of history. Mostly they are under-used. The idea that audiences can write their own ending is appealing, but in my experience, people will often be more inclined to seek out a cup of tea than write something meaningful. Where I have seen it work, it’s all about the prompt. You have to ask the right question.

2. The big finale

Another strategy is to take a lesson from film or theatre and end with a big closing number. My favourite part of the Opera exhibition at the V&A a few years ago was the finale: a super cut showcasing the diversity of operas from the past four hundred years, delivered on huge video walls with, needless to say, great tunes. And you know, I think the idea of the closing titles + stirring music could be used more, to good effect. At the very least, it conveys to audiences in a familiar way that this is the close and creates useful punctuation between one experience and the next.

3. The ending as beginning

In an effort to challenge my own understanding of narrative, I’m currently reading Finnegans Wake, the book that famously resists the idea of any kind of understandable storyline. Among its other idiosyncrasies, Finnegans Wake starts in the middle of a sentence and ends with the beginning of the same sentence. The ending is the beginning. I think this notion is often implied in our museum endings with some kind of invitation to go forth and discover more, but I think we could make it more explicit.

I’ve been struggling, ironically, with how to end this piece. I’ve asked more questions than I’ve answered. But as ever, the process of writing aloud has helped me to see a common thread. Delivering an ending requires intentionality. A great exit quote. A memorable image. A line drawn … for now.

Food For Thought

Frank Kermode’s The Sense of an Ending is one of those books I read as a student and now have come back to and realised how much it shaped my ideas about how we use narrative to make sense of the world.

I’ve just now come across this Radio 4 programme from January about rethinking the museum. Rethink: Museums

And because everyone loves a list, here’s a list of great cinematic endings: 15 Best Movie Endings of All Time, Ranked

And truly, if you have an example of a great exhibition ending … please let me know!

In 2023, Goddess was on at ACMI - it was an exhibition about women in film, and it had a great ending - as you walked out were a lot of clips of women leaving,, saying good-bye and telling you to get out. It really stayed with me - there is a little snippet of it at the end of this youtube vid: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35ka0NhPTZk

Counterpoint - people don't expect libraries to have an ending. They are more confident that a person arrives and seeks, fulfills their own question. What if it isn't about finding endings, but about resisting the idea of narrative at all; let's get rid of beginnings?

I am thinking of the Glasgow Transport Museum. there's no foyer, no introduction, you are just 'in' - and then there is no conclusion, just the exit door. All the way through, I watched visitors build their meanings and aggregate them into their own frameworks, and talking with each other to build meaning together.